This blog was originally hosted at Empty Cages Design.org as part of a series on Overcoming Burnout from 2016-2017. It has now been turned into a book that is available at: https://solidarityapothecary.org/overcomingburnout/

The following two posts were written after of a call-out for contributions from people who had experience of organising and participating in social struggles with a chronic illness.

Thank you again to everyone that has contributed. I have aimed to weave in as many words of other people as possible. Some people wish to be anonymous and I have used fake names with an asterisk while for others I have used their first names. Others are nameless and are simply integrated into the text without direct quotes.

There was so much material, this blog is in two parts. Part one, how it feels. Part two, what we can do to not leave people behind. Please note this blog focuses more on people’s negative/harmful experiences, part two focuses on inspiring examples of when people have felt supported and what we can do differently.

Introduction – Dismantling my ableist worldview

I have a lot of experience supporting partners, friends and family members with varying different illnesses, from bipolar, clinical depression and other mental health challenges, to chronic fatigue, being wheelchair bound and more. I’ve supported mates survive cancer and I’ve helped people I love leave this world.

I have a lot of experience supporting partners, friends and family members with varying different illnesses, from bipolar, clinical depression and other mental health challenges, to chronic fatigue, being wheelchair bound and more. I’ve supported mates survive cancer and I’ve helped people I love leave this world.

But until this year, I’ve never really been chronically ill. Colds, viruses, an appendix out and broken bones. But never a grinding long term illness, or the sense of despair that it evokes. Folks that have been reading my blog will know that I care a lot about radical honesty. And in this honesty, it is important to say that until this year I had no real understanding at all what my mates were really going through. I’d attend gatherings like Earth First! or Reclaim the Fields, and never be phased by camping or walking miles across rough ground. Late nights, early starts, long journeys, chronic stress – I felt like I could buffer it, almost thrive in it. I judged others for not keeping up with the pace. (Check out my When did I get so mean? chapter). I was totally and utterly stuck in an ableist perspective of the world. The normative body was my own – white, slim, ableness. All other experiences involved a more intelllectual kind of empathy, and in some ways a learned political performance (where I was always in the support role).

This blog, therefore, is about how it feels to be experiencing a chronic illness while being involved in social struggles. An inquiry into people’s experiences of illnesses developed through burnout or trauma and in relationship to engagement in movements, campaigns, organisations and collectives.

Deadwood?

What was upsetting about the emails I received was not so much the debilitation, pain and distress caused by actual illnesses – but the attitudes, reactions and lack of support in response from people identified as comrades and close friends.

Lyn is an incredible organiser who I have looked up to since I was a kid. Involved in SHAC (Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty) from day one, Lyn was brutally assaulted at the beginning of the campaign at an action blocking the A1 near Huntingdon Life Sciences. Pulled off a tripod more than 20ft high by police, Lyn was hospitalised with a broken leg, had more than 5 hours of surgery and experienced multiple complications. She was in a wheelchair for months and has had an array of after-effects, including PTSD and continuing chronic pain. Now Lyn has mild scoliosis, dizzy spells, permanent scarring, episodes where she can barely move (diagnosed as ME) and bursitis in her right hip after years of overcompensating for the left.

While Lyn’s story is a blog post (or book) in itself, I wanted to highlight some of the feelings she has experienced when still being heavily involved in the animal liberation movement with a disability, chronic illness and the aftermath of psycho-emotional health effects post-trauma. In terms of what has been traumatic, Lyn described some of the behaviour she has witnessed and been subjected to:

“Denial, ignoring it as though it hasn’t happened or is not in any way relevant to the campaign. Not being involved in decision making on how this should have been handled. The attitude that anything bad that happens during activism should be brushed under the carpet as to not put the “new people” off. The attitude that it is “weak”, “negative”, “harmful to the campaign” to cry or try and talk about what happened. The idea that there are those who make decisions and those who have to go along with those decisions, and an expectation that activists should do as they are told by other activists. It being intimated that I was not doing enough post being injured or when I have had periods of being unwell. Being told by some individuals that I let the side down by having a blood transfusion, anesthetics, and antibiotics which I would have died without. Some arbitrary cutoff recovery period by made by others.

Very little support long term, something cited by many activists whether they have been imprisoned, seriously injured, psycho-emotionally damaged by activism or all three. The term “deadwood” being used to describe those who have pushed themselves to exhaustion. Telling other activists that my injuries were minimal so that there would be no “negativity”. Being told that I play being a victim.”

Lyn’s words were painful to read, because SHAC, and the wider animal liberation movement, were my lifeblood for so many years. I was brought up in the movement, these people were my elders. I feel like I have spent the last 5 years since prison trying to unlearn all the harmful, abusive, problematic stuff I soaked up like a sponge during those years. (Don’t get me wrong, I also learned a lot of amazing things, and the movement was an antidote to equally shitty things in life). I am desperate to work for animal liberation but feel little affinity or safety any more engaged in struggles where experiences like these are endemic. I believe the movement has failed the animals, not because we didn’t work hard enough, but because we failed each other – we didn’t support each other during the repression, we didn’t look behind us when people burnt out. We lost hundreds of amazing people and their time, energy and passion because the work of caring for each other was not valued. No fucking more, ever again.

There is no binary between what gets called physical and mental/psycho-emotional health

There is obviously a brutal binary that capitalism cultivates, that somehow what gets called our mental or psycho-emotional and physical health are separate. I was expecting lots of emails about people’s “physical” health issues, but in fact, more and more were around social anxiety and feelings of depression.

The challenges that were highlighted included just how much it can affect someone who is struggling with their mental health to hear ‘relentless negativity’ and unending criticalness of each other and the tactics of different groups. Obviously critique is completely essential to learning, however, the effects of people slagging each other off, criticising and belittling others are draining and harmful, and can aggravate folks struggling with their psycho-emotional health beyond what we may know.

Likewise for those who experience social anxiety, trying to organise with people who dominate meetings or who are ‘extremely grumpy and who take their anger out on everyone around them unwarrantedly’ is really difficult, says Helen*. For a fellow comrade with experiences diagnosed as bipolar, they wrote how inflexibility is damaging. (In part two I talk more about how the way that organisations are structured can radically alter the feelings for people experiencing illnesses). Once again, organising with anxiety and/or depression is a blog post in itself, and one that I definitely don’t feel qualified to write.

Illness = Weakness?

The reproduction of that worldview that illness = weakness that our society perpetuates is a recurring theme in all of the contributions. Ali* told me, “Within movements, we seem to have fostered a culture of ‘illness = weakness’; showing that any signs of vulnerability are frowned upon, and we have to present ourselves as eternally strong warriors that feel nothing of the repercussions or draining effects of activism. As a result, we have ended up encouraging completely unhealthy, unrealistic, unsustainable and damaging way of campaigning and living; ways that actually write off long-standing campaigners or cause people to drop off the radar entirely. And how many times have we all heard about ‘burnout’?

This is not a simple byproduct of campaigning, but a direct result of our own attitudes as a movement and lack of understanding for how we exist and organise within various struggles… Illness is not a weakness. Feeling upset, feeling tired, feeling unwell are not anything to be looked down upon; it doesn’t make you less of an effective activist. What affects efficacy will be how we deal with these issues and how we manage our workloads.”

What is clear for folks with chronic illnesses is that a large source of anxiety is worrying what people think of them. For example, Helen* says people act like if you don’t go to X event, you don’t care about the issue. There is unending worry that they will be perceived as uncaring, uncommitted and apathetic simply because they can not be physically present at meetings and actions. Fears of being perceived as ‘lazy’ are frequent, even when they believe their comrades are ‘right-on’, have a good understanding of these issues or even illnesses themselves.

Am I a burden?

All the challenges we experience when organising – fear, stress, pressures on our relationships – all of these are aggravated by chronic illness. Ali* shares that “Chronic illness can also add to pre-existing feelings of helplessness and vulnerability that people often feel when involved in a struggle. It renders you unable to fight – not for others, and certainly not for yourself. Those feelings can be exaggerated further if fellow comrades are unsympathetic or make you feel bad about not being able to participate in certain activities.”

Those that contacted me also shared that they felt like they were ‘unwelcome burdens’. They are aware of their often more intense needs and don’t want to ‘burden people’, especially friends and comrades who are busy organisers. I have definitely felt unable at times to reach out to close friends that are comrades because I know how much pressure they are under. I have felt embarrassed and ashamed at times for needing to take a step back, for needing to admit I can’t do something or that I need support. For example, right now with my ribs, I can’t even carry a rucksack, for months I couldn’t even lift my laptop for fear of a flare up. I’d have to bashfully ask mates or mum to carry these things for me, and while only a small thing, these experiences, if not responded to with kindness and care, compound the feelings that you are useless, pathetic and needy. You hate yourself for ‘putting’ on people.

Fatigue and limited energy

Overwhelming contributions were those about fatigue. One person wrote that “disabilities that involve severe fatigue mean you have to ration your energy extremely carefully, often even for “small” things like going to the supermarket or having a meal with your housemates. Sometimes people, including activists, really don’t understand this at all and think that just because something is easy, even trivial, for them to do doesn’t mean I can necessarily do it right now. I can very rarely be spontaneous, and unexpected things can throw out my entire day or week. It’s not just a tiredness thing: when I run out of energy I completely lose the ability to communicate with most people and to complete basic tasks, and have to hide in my room until my energy comes back.”

Overwhelming contributions were those about fatigue. One person wrote that “disabilities that involve severe fatigue mean you have to ration your energy extremely carefully, often even for “small” things like going to the supermarket or having a meal with your housemates. Sometimes people, including activists, really don’t understand this at all and think that just because something is easy, even trivial, for them to do doesn’t mean I can necessarily do it right now. I can very rarely be spontaneous, and unexpected things can throw out my entire day or week. It’s not just a tiredness thing: when I run out of energy I completely lose the ability to communicate with most people and to complete basic tasks, and have to hide in my room until my energy comes back.”

When I was first sick with my costochondritis, I could maybe manage an hour a day of work before needing to lie down again. It meant I had to brutally ration my energy and therefore totally limit my involvement in all the collectives that had been the backbone of my life. And unfortunately, in capitalism, that energy must often first go to earning money so we don’t go under. For those with little practical support it might be making themselves one meal a day uses all the energy they have.

Feeling left behind

When needing to take breaks, at whatever timescales, people feel disconnected. And sometimes even punished for not being available or present. Involvement in a struggle is generative of relationships, connections and time with people you feel an affinity with. If illness = absence, then you lose a lot, sometimes even all of these relationships.

The most visible impulse in all of the contributions I read was that, more than anything, people do not want to be left behind. There is an overwhelming desire for people to be involved, to resist, to fight, to struggle. Sam* wrote, “Please don’t just avoid us and find somebody else to fill the gap we left, like we were only ever important as another body in the physical actions and resistance.”

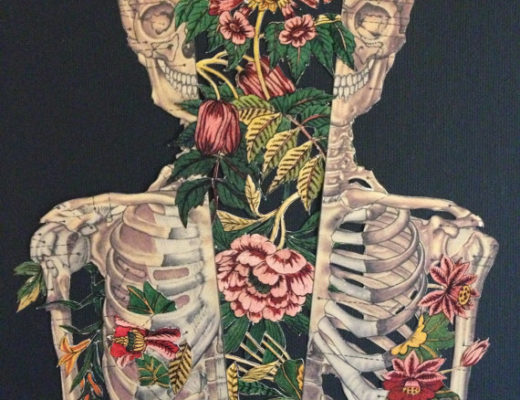

Living with a chronic illness IS revolutionary struggle

This next section could be a blog in itself. I wanted to end with an important point that was contributed by Aaron, a comrade of mine who shared their feelings from their years of experiences diagnosed as bipolar, and epilepsy:

“When I consider what “struggle” in a social, economic and political sense actually means, for myself at least, I begin from this quote from Raoul Vaneigem:

“People who talk about revolution and class struggle without referring explicitly to everyday life, without understanding what is subversive about love and what is positive in the refusal of constraints, such people have a corpse in their mouth.”

For many years, bipolar disorder and epilepsy have determined the form of my struggles. Remembering to eat, sleep, wash, go shopping, do the laundry, vacuum the floor, clean the kitchen and do the washing up or just, even after remembering, gathering energy to do at least one of them. Then, the flipside – having too much energy and being reckless, arguing and fighting strangers, spending money that’s not even mine, trying not to lose too many friends. On top of this, worrying that I may have a seizure and walk into a main road, again. But I have to live my life and it has been the drive to go beyond the everyday constraints thrust upon me by poor health that has brought me in to direct conflict with the crippling insanity of capitalist social relations.

How I’ve chosen to struggle against this has also been defined, not just by the current state of revolutionary and radical social struggles but the form they’ve taken. My ability to participate in particular struggles is fundamentally down to how they are organised, how much this organisational practice enables me to participate.”

No Comments