Please note these plant profiles are a work in progress. I will always be adding to them as I keep learning about the amazing world of plant medicine.

Botanical Overview

Latin name: Malva sylvestris

Plant family: Malvaceae

Identification: Tall and upright (to 1m) or rather creeping. Leaves are up to 12cm across with broad lobes, long stalks and commonly a dark spot on the base of the leaf blade. Flowers are 2.5 – 4cm across (1). Mallows have five flower petals. The flowers of common mallow are whitish to light pink in colour and have pink stripes running up each petal on the flower. Mallow flowers are bisexual, meaning both the female and male reproductive plants are in each flower. In the centre of the flower, the pistil sticks out. The ovary is located at the base of the petals and eventually ripens to produce the cheese wheel-like fruits. The fruits are circular and look like a miniature round block of cheese (2).

Other species: The most commonly used species of the mallow family for medicinal purposes is Marshmallow (Althaea officinalis). However, there are many related useful species including dwarf mallow (Malva neglecta), cheeseweed mallow (Malva parviflora), bull mallow (Malva nicaeensis), dwarf mallow (Malva rotundifolia), hibiscus (Hibiscus spp.), hollyhock (Alcea rose), desert scarlet globe mallow (Spaeralecea coccinea), okra (Abelmoschus esculentus), Indian mallow (Abultilon incanum), Chingma (A. theophrasti). Cacoa and cotton are also in the mallow family. Other species of the British Isles include Cornish Mallow (Lavatera cretica), rough mallow (Malva setigera) and Tree mallow (Lavatera maritima).

Folk names in English: High Mallow, Tall Mallow, Blue Mallow, Cheese-cake. Malva comes from the Greek word “malaxos”, meaning slimy, or to soften.

Chemical constituents: Flavanoids, mucilages, Terpenoids, Phenol derivatives, Enzymes: sulphite oxidase, Coumarins, Vitamins: tocopherols (vitamin E) and ascorbic acid (vitamin C), Fatty acids/sterols. Pigments: chlorophyll A, chlorophyll B and xanthophylls (3).

Food and nutrition

The leaves, flowers and roots have a long history of edible use spanning continents over thousands of years. The leaves can be used as a vegetable. They are a great thickening addition for soups. The flowers can be added to salads. Mallow water has been used as a vegan egg substitute. The root can also be blended with water and then strained to make a creamy nutritious plant milk (2). Mallow is high in calcium, vitamin A and iron, as well as dietary fibre, magnesium, selenium and vitamin C (4).

Ecological role

Common mallow is commonly found on waste ground, footpaths, meadows, moist ground and road sides. Mallow’s strong roots can help aerate and fertilise degraded soils. Katrina Blair writes how mallow can be a great ‘midwife’ to other plants, as well as how mallows can be susceptible to several fungal colonies, including mallow rust, which causes dark orange coloured bumps to appear on the underside of leaves. The cause of this fungus is often from an overly moist environment and a dense thicket of mallow (2). Herbalists Julie and Mathew Seal highlight that the low-growing leaves tend to accumulate heavy metals from vehicle exhausts (5).

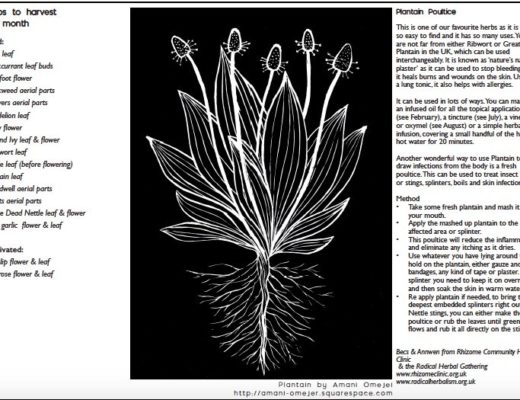

Drawn by Amani Omejer for my upcoming Prisoner’s Herbal book

Cultivation and Harvesting: Mallow is very easy to grow from seed and is adaptable to most soils. Mallow leaves are best harvested when the stems are bright green and healthy looking (beware of rusted leaves). It’s ideal if the plants can be used fresh because of their water and mucilaginous content, however, they can be dried too (they will loose about one third of their mucilaginous qualities). The roots are best harvested in the autumn when they have more mucilage. On a broader scale, according to herb farmers, Melanie and Jeff Carpenter, the roots are usually quartered, washed and partially dried for 36 to 48 hours to remove at least 25% of their moisture. After this par drying period these roots can be milled into large pieces approximately half and inch in diameter and spread out on racks again in the drying shed to complete their drying process (6).

Energetics

- Temperature: Neutral to cooling depending on constitution

- Moisture: Moist

- Tissue State: Dry/atrophy, heat/excitation, wind/tension

- Taste: Sweet and salty

Health challenges supported by Mallow:

Herbal actions: Antibacterial, mild astringent, anthelmintic, demulcent, diuretic, laxative, emollient, expectorant, inflammation modulating

J.T. Burgess wrote in 1868 that “The Uses of Mallow are infinite” (2). The fresh or dried leaves are best infused in cold water (to preserve the mucilaginous content), and drunk for the treatment of the digestive, respiratory and urinary tracts. A fresh herb and root tincture can also be made, however, these mucilaginous herbal action will be significantly affected. Some of the health challenges supported by common mallow include:

Digestive issues: Mallows are mildly astringent, which means they help to tone the mucosal membranes and the skin. It also has a vulnerary action with an ability to staunch mild bleeding. Combined with its soothing, emollient and moisturising properties, you can see why it is useful for people have patterns of heat and inflammation in their digestive tract. This includes ulcers, gastritis, colitis, and entiritis, as well as Chron’s disease. It can also support people recover from leaky gut syndrome, commonly caused by prolonged use of non steroidal anti inflammatories such as aspirin. Mallows, marshmallow in particular, can also support with GERD and issues of gastrointestinal reflux. In digestive challenges, the tea (or strong herbal infusion) is most effective as you want to cover as much surface area as possible. Avoid dry powders, as the power is in the moisture! Likewise, for inflamed conditions such as haemorrhoids, mallow can bring relief. Herbalist Sajah Popham recommends sitz baths especially (7).

Respiratory infections: The herb is a powerful demulcent for coughs, colds, sore throats, asthma and chest troubles. Sajah writes that marshmallow (the most commonly used member of the mallow family) “soothes, clams, cools and moisturises a respiratory system that is overly inflamed, hot and tense. It tends to relax excessive spasm in the smooth muscles lining the entire tract and increase mucous secretions from the membranes. Marshmallow is for respiratory conditions that are hot and dry.”

Sore throats: Mallow can help soothe sore throats, especially those that are hot and dry and in need of moisture and cooling. The flowers are commonly made into a syrup for this purpose.

Urinary tract infections: In a similar way to the above, mallow helps to soothe the inflamed tissues in the mucosal membranes of the urinary tract. The leaves, rather than the roots, are more commonly used for UTI infections and they also have a diuretic effect. Marshmallow is commonly used by herbalists to help relieve conditions such as cystitis, urethritis and nephritis.

Toothache: Mallow flowers can be chewed to relieve toothache.

Insect bites, boils and abbesses, sores, cuts, bruises or general skin complaints: You can chop or chew the fresh leaf and apply directly as a poultice.

Burns: Marshmallow leaves (but any mallow leaf you can access in an emergency) have also been used in traditional burn care (after common first aid practices are followed). Mallow leaves traditionally have been combined with olive oil for the prevention of blistering (8).

Cosmetic skin care: Katrina Blair says that “Mallow is celebrated in our community as one of the best skin repair remedies around. As a face wash and healing mask, it repairs sun damage and rejuvenates the skin. It makes a wonderful green facial mask that removes skin blemishes and irritation amazingly quickly.” (2) Mallow leaf and flower can also be made into herbal oils to soothe and regenerate the skin.

Sore or strained eyes: Mallow can also be made into an infusion for bathing inflamed eyes (9).

Musculoskeletal system: While not famous for its affinity with the musculoskeletal system, many herbalists include mallow in their mixtures because of its moistening effect on people with joint pain linked to dryness. Also, as a lot of musculoskeletal issues can be linked directly to inflammation in the gut (in the case of my rib cage, food intolerances were a major culprit) and mallow can support inflamed tissues.

Immune system: Another less known affinity of mallow is its support for the immune system because of its actions on the mucous membranes. Sajah describes how “The presence of polysaccharides indicates an immunological quality, as commonly these sugar compounds are seen as similar to bacteria or other pathogens by the immune system, thus triggering it into a heightened state of activity. It’s also important to remember that the mucosa is laden with white blood cells and immunity to protect the body from pathogenic invasion. Thus by simple virtue of increasing mucosal secretions immunity is enhanced.”

Cautions: In large doses, mallow can be laxative and purgative. While it can take a while to get to grips with the concepts of energetics, it is important to remember that mallow is not ideal to give to people with cold/wet/damp conditions.

Mallow and the Solidarity Apothecary

Mallow will be featured in the upcoming Prisoner’s Herbal book that I am writing. It was one of the few plants growing in the waste ground of the prison where I was. I would nibble on the flowers and use the poulticed leaves on cuts and scratches on my arm from working outside in the prison courtyard. Herbalists without Borders use marsh mallow in cough syrups given out in large quantities in Calais and Dunkirk, as many houseless refugees and migrants have chronic respiratory issues.

Sources

1. Plants and Habitats, Ben Averis

2. The Wild Wisdom of Weeds, Katrina Blair

3. http://flipper.diff.org/app/items/info/5518

4. Nutritional Herbology, Mark Pedersen

5. Hedgerow Medicine, Julie Bruton-Seal and Mathew Seal

6. The Organic Medicinal Herb Farmer, Jeff and Melanie Carpenter

7. Marshmallow monograph, Materia Medica Monthly produced by the Sajah Popham at the School of Evolutionary Herbalism

8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3941892/

9. https://botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/m/mallow07.html